Learning Blackjack with Monte Carlo Reinforcement Learning

Testing different monte carlo reinfrocement learning methods to learn the optimal strategy for blackjack.

Overview

When played correctly, blackjack is a great casino game because of its relatively high, albeit still negative, expected value. On top of that, playing correctly isn’t reserved for an elite few strategists. The strategies are openly available online and it isn’t hard to memorize them. Here’s an example of one right now:

In this strategy, you look up which state you’re in (based on your hand and one card of the dealer’s hand) and then choose the appropriate action, either stay or hit.

Once you dive a bit deeper into these websites you may realize blackjack doesn’t exactly follow the same set of rules everywhere. Each place has its own set of house rules. Some games differ on when a dealer will stop hitting. In addition, some games give you the additional actions of surrender, double, and split. And before you even draw your cards, some games give you the choice of buying insurance. And on top of all of that, many games have differnt payouts for blackjacks. Suddenly you realize there are countless permutations of this seemingly simple game and each one likely has a slightly different optimal strategy.

Finding the optimal strategy for your given game of blackjack is now a much more difficult endeavor. It’s possible that you can find it online with some digging, but if you’re not familiar with the particular website that has your version of blackjack, you may question strategy’s credibility. To be completely sure, it’d be ideal to derive the optimal strategy yourself. While it is possible to iterate through each possible outcome and even use some probability to simplify the problem, it’s also possible to derive the best strategy in a slightly more efficient and generalizable manner. This is achievable through reinforcement learning methods. In particular, monte carlo methods are especially well suited for blackjack since both well aligned to episodes, or independent, single instances of a game. Monte carlo methods perform value and policy updates at the end of each episode and blackjack only reveals the reward, or payout, at the end of an episode.

In this post, I’ll experiment with a few variations of the Monte Carlo methods using a very simple version of blackjack and talk through these areas:

-

Setting up the Reinforcement Problem

-

Different Monte Carlo Methods and Settings

-

Results of Using Different Methods and Settings

-

Next Steps to Expand to More Complicated Blackjack Games

Setting up the Reinforcement Problem

In order to set up the reinforcement learning methods, it is first necessary to define a few components of reinforcement learning and show how blackjack fits into them.

First, let’s describe the environment of the game. In reinforcement learning problems, there’s an interface between agents and the environment, where the agent is interacting and learning within some environment.

-

Agent: The agent is the learning and decision maker in the problem. In blackjack, the agent is the player

-

Environment: The environment is everything outside the agent, where the agent doesn’t full control. In blackjack, the environment is the dealer and the cards being drawn

Now let’s briefly describe how the agent interacts within this environment by defining their different states and actions.

-

States: These describe unique scenarios of where the agent is within the environment. In blackjack, this can be neatly defined as the player’s hand and the dealer’s card. To transcribe that into unique entries in a table, we’ll consider three variables: the sum of the player’s hand (4-21), whether the player has a usable ace (0 or 1), and the dealer’s card (1-10)

-

Actions: At each state, the agent must perform one action. In blackjack, players often can choose to stay, hit, double down, or split. For simplicity, we’ll consider only the first two actions of staying and hitting, which we’ll encode as 0 and 1.

To enable the agent to learn and act, there are typically 4 components to define in a reinforcement learning problem:

-

Policy: Defines the agents way of behaving at a given time. In blackjack, it’s the strategy that the player follows based on their state (which consists of their cards and the dealer’s card)

-

Reward Signal: Defines the goal of a reinforcement learning problem. In blackjack, it’s the player’s winnings or losses at the end of the game

-

Value Function: Estimates the expected rewards from that point onwards. In blackjack, it’s the expected winnings or losses for a given state

-

Model of Environment: Mimics behavior of the environment in which the problem takes place in. Monte carlo methods don’t require a model, so we won’t consider this component for this problem

Now that we’ve defined the core components, we can apply them to a Monte Carlo method.

Different Monte Carlo Methods and Settings

Similar to the countless variations of blackjack, there are countless variations of Monte Carlo methods. To start off, we can dichotomize Monte Carlo methods into on-policy and off-policy methods:

- On-policy methods learn and play using a single policy

- Off-policy methods use separate policies to learn and play

WIthin on-policy methods, we’ll experiment with a few parameters:

-

Initial policy actions: Does the initial actions affect convergence and performance? Are they best set at 0, 1, or at random?

-

Initial values: Does the initial value of each action for each state affect convergence and performance? Are they best set at low, average, high, or random values?

-

Rate of exploration: How often, if at all, should the policy deviate to test different actions?

Within off-policy methods, we’ll experiment with a slightly different list of parameters to account for the inherent testing built into the methodology:

-

Initial policy actions: Does the initial actions affect convergence and performance? Are they best set at arbitrary actions or at random?

-

How to weight learnings: Does ordinary or weighted importance sampling have better convergence and performance?

For each of these methods, I’ll run at least 50,000 games to assess the average winnings of the final policy and the time (i.e. number of games) it took to converge on that policy. I plan to compare these methods amongst each other and also against some pre-defined policies found online.

Results of Using Different Methods and Settings.

Starting with the on-policy methods, I first evaluated the different policy and value settings and found the best results with arbitrary initial actions and optimistic initial values:

| Initial Actions | Initial Values | Average Winnings | Time to Convergence | |||

| Arbitrary | Average | -0.160 | 25,000 Games | |||

| Arbitrary | Optimistic | -0.113 | 20,000 Games | |||

| Random | Average | -0.126 | 20,000 Games | |||

| Random | Optimistic | -0.151 | 25,000 Games |

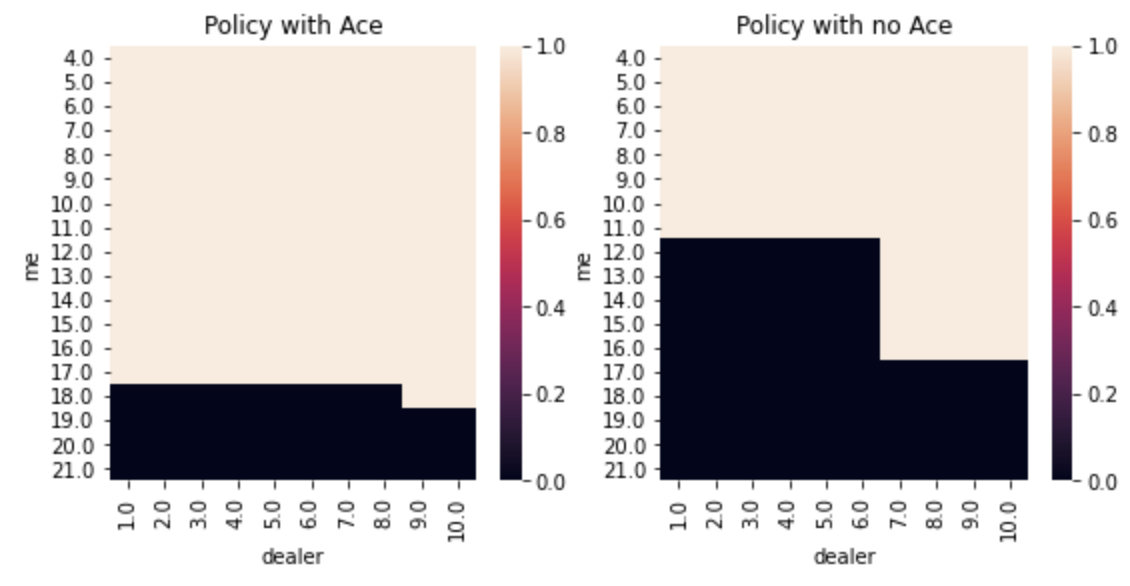

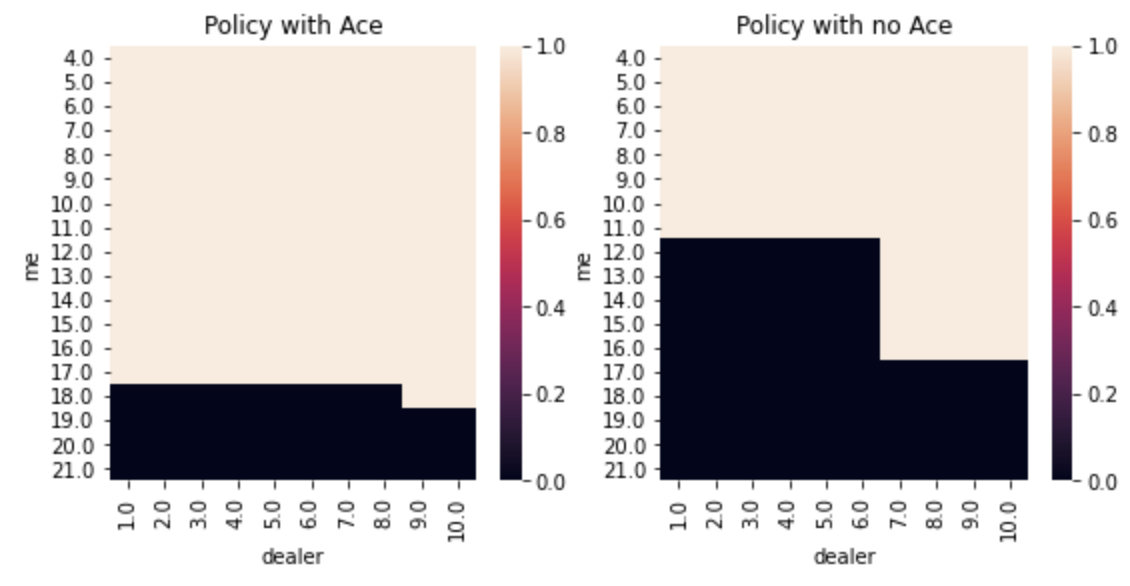

Here’s what the policy looked like for the best on-policy method without any exploration:

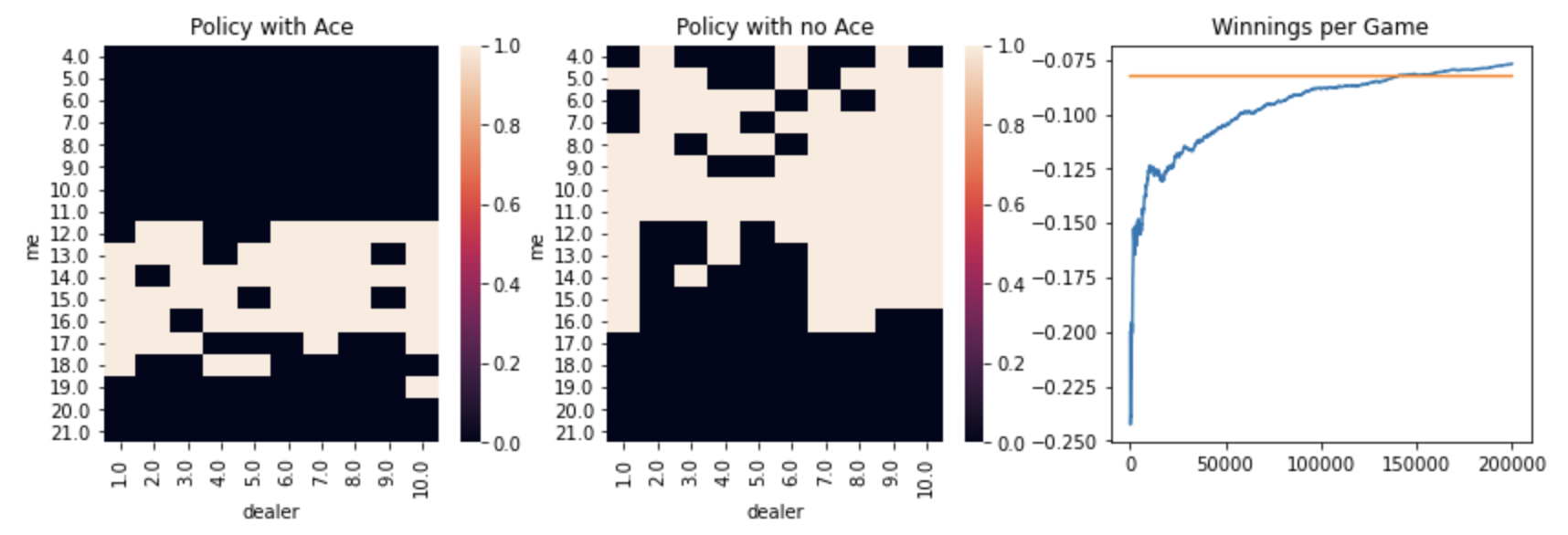

I then used the settings of that winning method, arbitrary initial actions and optimistic initial values, and tried different rates of exploration (called epsilon) to see if that could further improve performance:

| Epsilon | Average Winnings | Time to Convergence | ||

| 0 | -0.113 | 20,000 Games | ||

| 0.05 | -0.077 | 200,000+ Games | ||

| 0.10 | -0.082 | 200,000+ Games | ||

| 0.20 | -0.109 | 200,000+ Games |

For these on-policy methods with a non-zero rate of testing, the rate of convergence slowed considerably. Even after 200,000 games, all of these non-zero rates showed continuous improvement. Despite not reaching full convergence, the method using an epsilon of 0.05 had the highest average winnings and also showed the steepest slope of improvement over time. Here’s what the policy looks like and the winnings over time:

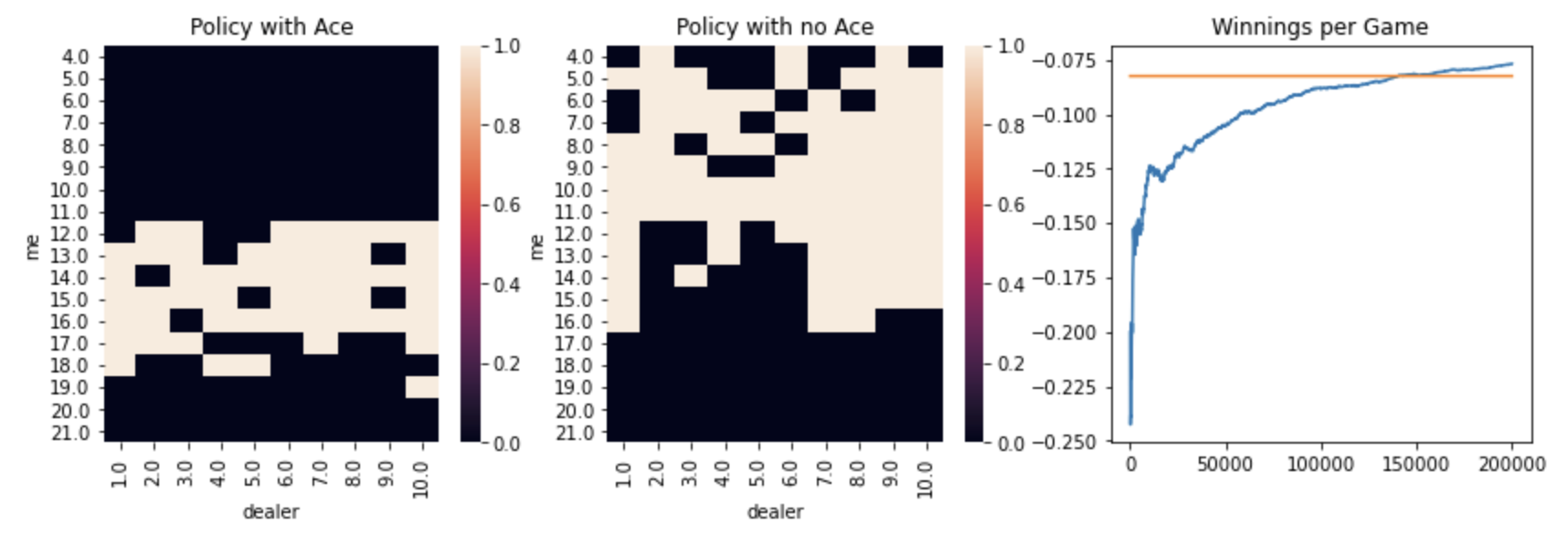

Separately, I evaluated different off-policy methods using different initial actions and weighting methods:

| Weighting | Initial Actions | Average Winnings | Time to Convergence* | |||

| Ordinary | Arbitrary | -0.205 | 30,000 Games | |||

| Ordinary | Random | -0.151 | 30,000 Games | |||

| Weighted | Arbitrary | -0.043 | 20,000 Games | |||

| Weighted | Random | -0.070 | 30,000 Games |

- Number of games simulated through off-policy

For this comparison, the weighted importance sampling with arbitrary initial actions performed the best, having the highest winning and quickest convergence of all methods considered above. It is worth noting the difference in time to convergence between on-policy and off-policy methods. For off-policy methods, you have to simulate games through both the on-policy and off-policy, which requires more resources and time. Either way, this off-policy method converged much more quickly than the epsilon-based on-policy methods above. Here’s what the policy and convergence looked like for the weighted importance sampling with arbitrary initial actions:

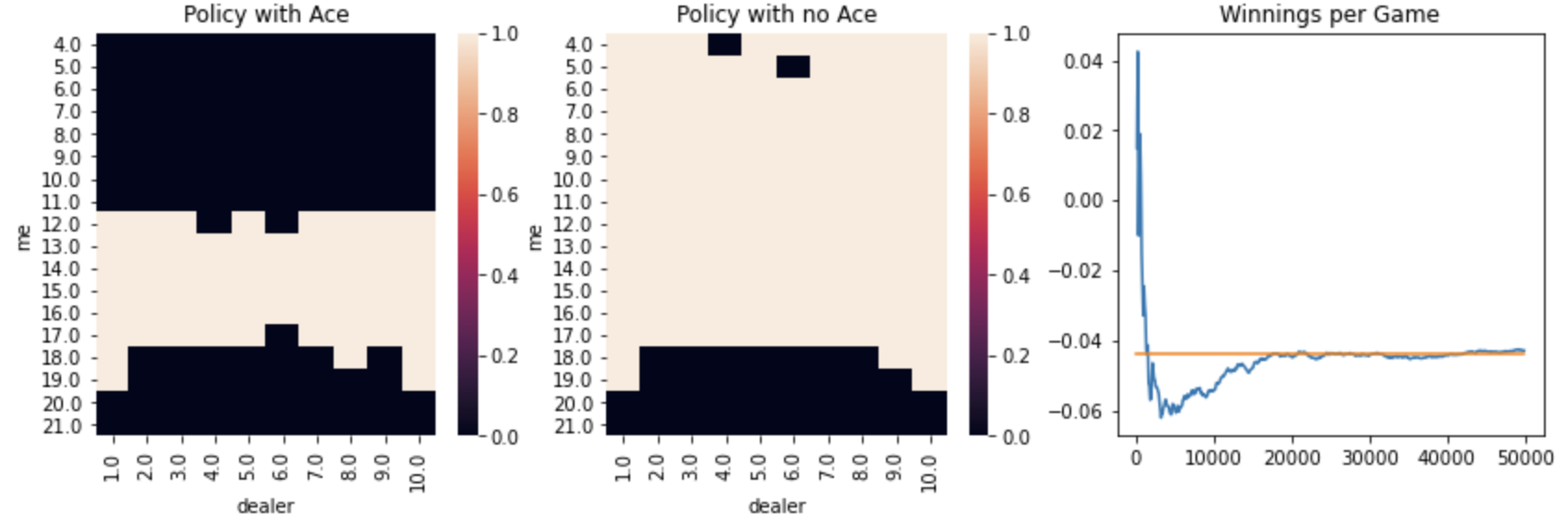

Finally, I compared this to some off-the-shelf policies, such as this one:

To get a sense of how optimal the epsilon-based on-policy methods above could be if I ran more trials, I also ran this off-the-shelf with different testing rates:

| Epsilon | Average Winnings | |

| 0 | -0.023 | |

| 0.05 | -0.041 | |

| 0.10 | -0.065 | |

| 0.20 | -0.094 |

Next Steps to Expand to More Complicated Blackjack Games

Though this post showed how generalized reinforcement learning methods can be used to learn a simple game of blackjack, there are two main gaps between the results and walking into a casino using these strategies.

First, the recommended strategies were not optimal. Given the off-the-shelf policies performed better, the reinforcement learning methods likely needed more trials to converge on the optimal policy. Due to processing power and time limitations, it’s not always possible to get enough trials to reach that optimal policy. This issue is compounded by the next gap in game complexity.

For this post, I picked a relatively simple version of blackjack that did not include any options to double down or split. In many variations of blackjack where these actions are allowed, it is advantageous for the player to use them in particular scenarios, which enables the average winnings to slightly increase. Furthermore, it’d be more advantageous to incorporate more data into the states that describe the remaining cards in the deck. Many blackjack games advertise how many decks are in play (from 1 to infinite via constant shuffling), so there’s likely some additional information and value in knowing the remaining cards in the deck.